X

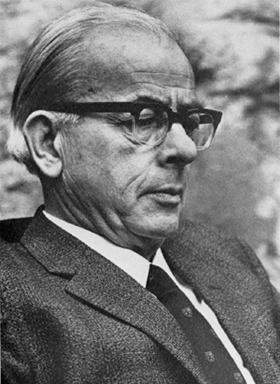

Howard Everest Hinton

|

|

Howard Hinton was born in Mexico of British parents, and went to schools in Mexico and California. His undergraduate work was done at Berkeley and his postgraduate work at Cambridge, where he took the Ph.D. in 1939 and the Sc.D. in 1957. He was an Assistant Keeper at the British Museum (Natural History) (1939-49), then successively Lecturer, Reader, and Professor at the University of Bristol. He published a huge volume of papers and several books on insects and other animals, principally in the fields of taxonomy, functional morphology, and natural history.

During his undergraduate years he began to publish short papers on the collection and identification of beetles, and by the time he graduated B.Sc. in 1934 he had already published 17 papers. He is remembered by his contemporaries for his blunt manner and forthright expression of opinion. On completing his work for the Ph.D. in 1939, Hinton was appointed an Assistant Keeper in the Department of Entomology at the British Museum (Natural History), where he was to have been assigned to identify Orthoptera. But he spent the war years in the Infestation Branch of the Ministry of Food working at first on beetles then on other insects infesting stored products. At the Museum he became a legend for his devotion to work, camping beside his bench during the blitz.

In 1949 Hinton was appointed Lecturer in the Department of Zoology at

Bristol, and in 1951 was advanced to Reader. Hinton's industry was phenomenal. He worked with great intensity for very long hours, night and day, and during the decade 1951-60 he published 51 papers. During the second decade of his life at Bristol, Hinton's international reputation grew rapidly as his publications attracted the attention of workers in more and more fields of entomology. He was invited with increasing frequency to take part in symposia and to speak at international conferences. His scientific distinction was recognized by his election to the Royal Society in 1961, and the University of Bristol established a personal Chair for him in 1964. Throughout the period he continued to teach, to edit an expanding journal, and to publish research at an astonishing rate-his bibliography includes 56 items published in the years 1961-70.

In this period he accepted several invitations to travel abroad, largely during

vacations, for he never took sabbatical leave from his university duties. He

visited China for two months in 1960 as the guest of Academia Sinica, giving

lectures in Peking, visiting research laboratories in several cities, and collecting

insects as opportunities occurred. The following year he lectured in Prague as a

guest of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, and spent ten days in discussion with research workers at several centres. In 1963 he was awarded a

Senior Fellowship of the Australian Academy of Sciences and subsequently

published a monographic revision of the Australian species of Austrolimnius.

He made a brief visit in 1965 to Ahmadu Bello University in northern Nigeria

and added some productive collecting to his duties as examiner. For two weeks

in the spring of 1968 he represented the Royal Society in an exchange of visits

between the Society and the Academy of Sciences of Bulgaria, and between

formal engagements found time to collect four specimens representing a suborder of beetles new to the fauna of Bulgaria. He attended the National Congress of Entomology in Mexico in 1967, and in 1969 spent four weeks there under the Latin American program of the Royal Society, a week representing the Society at meetings in Mexico City and three weeks collecting beetles (over 5500 specimens) at Cuernavaca and near Acapulco.

He became Head of the Department of Zoology at the University of Bristol in 1970 and served in this capacity until his death in 1977. He served as President of the Royal Entomological Society for the two years 1969 and 1970, and as President of the British Entomological and Natural History Society in 1972. Early in the summer of 1971 he went to a conference in Venezuela and collected for a few days in the Eastern Cordillera of the Andes; and in September he was again the guest of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. In 1972, after attending the International Congress of Entomology at Canberra, he spent a month collecting insects in New South Wales and Queensland. The Institute of Ecology of Mexico invited him to be an Honorary Associate and offered him facilities at the stations they had set up in different parts of Mexico; in consequence he went to Mexico in 1970, 1974, and 1976 and, besides lecturing and taking part in discussions, he was able to engage in the sort of field work that he so much enjoyed.

In 1975 he was found to have a tumor, for which he underwent surgery, apparently successful. He was briefly elated at his escape and carried on all his former activities, including another visit to Mexico. He attended the International Congress of Entomology in Washington, D.C. in 1976. But things were not right, and by November1976 he knew that he had not long to live. He tried to let it make no difference and continued his work to the end, going to the Laboratory until five days before he died on 2 August 1977.

Although he eventually became a very knowledgeable naturalist with broad

interests, Hinton's biological activities were at first and for several years those

of a collector, principally of beetles. Many of the species he found were undescribed, the fauna of Mexico being then imperfectly known, and with characteristic self-assurance he began to describe and name them himself. 'My first paper', he wrote, 'was published in 1930 and by the time I graduated in 1934

I had published 17 papers on the taxonomy of beetles. The restriction of his interest to this field continued for a surprisingly long time. The first 57 papers he published are on beetles, and all but one are mainly about their identity and classification. Hinton was moved out of this narrow specialization by circumstances rather than by choice. His war-time work at the British Museum, principally on insect pests of stored products, had immediate results in the form of useful papers on beetles of the families Lathridiidae, Histeridae, Ptinidae, the genus Tribolium. and a valuable monograph of 443 pages on beetles

of all kinds associated with stored products.

Hinton's personality was expressed in some of his scientific papers. His writings are usually direct and clear; they are sometimes marred by dogmatic and even arrogant statements. The dogmatism was probably a development from his self-confident boyhood, and may have been fostered by his 20 years as a taxonomist ('A species is good if a competent taxonomist says it is'). He wrote with enthusiasm, often in excitement, and sometimes failed to make it clear whether he was stating a fact that he had established or a firmly held opinion. Unfortunately, in some of his papers he seemed to go out of his way to offend workers whose views he did not accept. Hinton's polemics drove him to

produce a vast amount of information and argument which threw light on old

problems and opened up new lines of investigation. Hinton published taxonomic papers over a period of 48 years, describing and defining many new genera and very many new species of insects, mostly but by no means all in the Coleoptera. He was undoubtedly the world's leading authority on the Dryopoidea.

His relish of controversy, and the vigor with which he pursued it,

gained him a reputation as a scientific polemicist. He enjoyed that view

of himself, and it may be that in living up to it he went farther than he would

otherwise have done. A few of his papers, some of them among his last, contain

not only argument but invective. He was certain that he was right; and in

controversy he felt it was his duty to gain his point because in so doing he was

establishing truth. He was unwilling to accept received opinion, he enjoyed the

effect of questioning dogma, and he had no hesitation in challenging the

'Establishment'. Such feelings as these explain his entry into disputes, but they

do not justify the tone of his disputation. When he found he was wrong, he admitted his mistake frankly and corrected it in print.

Reference for above description:

Salt, G. 1978. Howard Everest Hinton. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 24: 150-182.

|